Ten years ago, essentially the only people thinking hard about distributed tracing were academics and a handful of large internet companies. Today, it’s turned into table stakes for any organization adopting microservices. The rationale is well-established: microservices fail in surprising and often spectacular ways, and distributed tracing is the best way to describe and diagnose those failures.

That said, if you set out to integrate distributed tracing into your own application, you’ll quickly realize that the term “Distributed Tracing” means different things to different people. Furthermore, the tracing ecosystem is crowded with partially-overlapping projects with similar charters. This article describes the four (potentially) independent components in distributed tracing, and how they fit together.

Distributed tracing: A mental model

Most mental models for tracing descend from Google’s Dapper paper[1]. OpenTracing[2] uses similar nouns and verbs, so we will borrow the terms from that project:

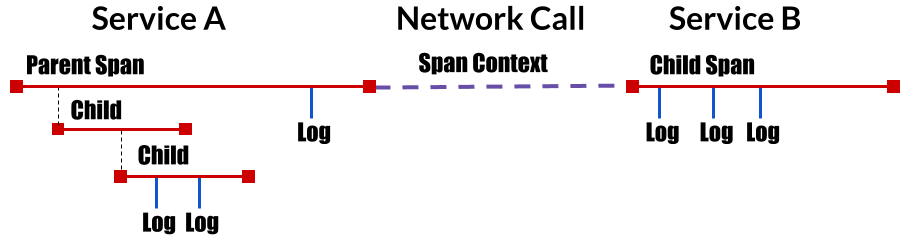

- Trace: The description of a transaction as it moves through a distributed system.

- Span: A named, timed operation representing a piece of the workflow. Spans accept key:value tags as well as fine-grained, timestamped, structured logs attached to the particular span instance.

- Span context: Trace information that accompanies the distributed transaction, including when it passes from service to service over the network or through a message bus. The span context contains the trace identifier, span identifier, and any other data that the tracing system needs to propagate to the downstream service.

If you would like to dig into a detailed description of this mental model, please check out the OpenTracing specification[3].

The four big pieces

From the perspective of an application-layer distributed tracing system, a modern software system looks like the following